(This article is 3,051 words long and takes about 12 minutes to read. Click here to download it as a .pdf to save to read later / print.)

—

It’s been almost two months since The Obvious Choice was released. Lots of people have been asking me how it’s been going.

If I’m honest, my answer is “not great”.

I’ve been disappointed with sales and so has my publisher.

What makes it harder to swallow is how good the feedback has been––almost unanimously. People who have read or listened to the book have loved it. The reviews across both Amazon and Goodreads reflect this.

The problem is that not many have given it a chance.

This disconnect between quality and reach isn’t unique to books. It’s the universal challenge of any worthwhile creation: how do you get your best work in front of the right people?

I’m not an exceptional person, but I am a grower. I do have the ability to look at my shortcomings and improve for the future.

I’m sharing five crucial lessons I’ve learned from this experience. Not to complain, but to illuminate the path for anyone bringing something valuable into a noisy world.

Whether you’re launching a product, sell a service, or creating art––these five lessons transcend any specific field.

1. Positioning: The Art of Framing Value

People buy business books because they’re hoping for frameworks to solve their immediate problems (getting more leads, improving sales, scaling staff.)

Choice isn’t like that. It’s a self-help book disguised as a business book.

It’s about finding your way in a world gone mad. One that’s designed to distract you.

But, it was positioned as a book to help you make more money. And, honestly, I underestimated just how little the world wants another business book.

This applies beyond books. The fitness instructor who positions their service as “building a better body” versus “creating sustainable health habits” will attract entirely different clients, even when the actual training is identical.

If somebody knows that they have a problem, they’ll buy the solution. General information, irrelevant of how useful it is or how much a person needs it, doesn’t sell the way it used to. Distraction and overwhelm are too strong forces.

In my case, everybody these days wants to know how to build a bigger and more engaged following on social media.

I wrote a book that, in large part, tells them that that’s a waste of time.

Which I still believe to be true.

But nobody wants that. Nobody is waking up in the morning and looking in the mirror and saying to themselves, “I hope somebody tells me that this thing I’m working hard on and stressing over is a waste of time and presents a different way.”

The way your book, product, or service is framed determines who finds it and how they engage with it. My mistake wasn’t just about marketing; it was about clarity of purpose.

Ask yourself: What problem does your audience believe they have versus what problem you’re actually solving? The gap between these two perspectives often determines success or failure.

A few questions to filter your positioning through:

- What’s your audience searching for right now?

- What language do they use to describe their challenge?

Figure this out by looking at headlines of magazines that serve your audience, the language used in bestselling books, or the content shared by the top thought leaders that market to your people. Then go one step deeper and read comments on their posts and write down the words and phrases actually being used.

In my case, I created a thoughtful exploration of finding purpose in a distracted world but packaged it as just another business growth manual. I missed the sweet spot.

Once people read it they get it. But, they have to read it to get it.

People say not to judge a book by its cover. Which is ridiculous. Of course you should judge a book by its cover. That’s why books have covers.

Getting the positioning right is only the first step. Even more important is ensuring you’re speaking to the right audience in the first place.

2. Audience: Quality > Quantity

In Choice, I write:

“If the way you’ve built an audience is inconsistent with the product or service you want to sell, you’ll end up rich with likes but poor with dollars.”

I anticipated that I’d have this problem. Even called it out in the book.

A part of me is happy because my experience has proved out the lesson from the book.

Another part of me is upset because of just how true this lesson has proven to be.

Having thousands of followers who don’t convert into customers isn’t just a business problem; it’s a fundamental misalignment between who you’ve attracted and what you’re offering. The metrics that feel good (followers, likes, subscribers) can become a mirage that obscures the metrics that matter (engagement, conversions, revenue).

I’ve built an audience online of people who work in fitness over the last 15 years. For the most part, people who work in fitness are disinterested in the business.

They might say that they want to grow their business. But then they’ll buy a seventh course having to do with fitness or nutrition before seriously studying anything to do with business or marketing.

Which I totally get.

They love fitness. They don’t love business.

Here’s another passage from The Obvious Choice that bears repeating:

Superficial engagement metrics such as likes, comments, shares, and followers are all measures, not targets. Relying on them as your only insights is like playing a game with no scoreboard.

In my coaching company (The Online Trainer Mentorship), we track how many inbound direct messages inquiries are received.”

Many of us build our platforms backward. We create content that’s easily consumable, build an audience around it, then try to sell something that doesn’t align or requires a different level of commitment. The strongman lifting logs over his head for likes on social media that “trains new moms”. The 21-year old ripped influencer who helps “busy parents”. The entertainer who comes out with a flavoured water supposed to help you workout harder, focus better, or hydrate more––as if any of those things solve the underlying problem.

As John Delony says, “If your house is on fire and there’s an alarm going off, it’s not the alarm that’s the problem.”

The result’s predictable: an audience that loves what you say but doesn’t value what you sell.

Don’t ask “How do I convert my existing audience?”

Instead, ask “How do I begin attracting the audience that aligns with my true purpose?”

I’ve made some changes since Choice was released to better align my platforms with my work. As a result, my audience has shrunk.

My email list has lost over 6,000 subscribers. Instagram’s down 5,000+.

While seeing the numbers go down can be hard to swallow, I know the truth:

“Metrics are a like a spotlight,” said Jonah Berger, a marketing professor at the Wharton School and the New York Times best-selling author of Contagious: Why Things Catch On.

“They shine attention on something. If that’s what we want to optimize, great. But if it’s not, we need to be careful because it may encourage us to optimize whatever it’s focused on.”

Goodhart’s Law states, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Superficial engagement metrics such as likes, comments, shares, and followers are all measures, not targets. Relying on them as your only insights is like playing a game with no scoreboard.

I’m still hopeful that the book will expand outside of the fitness industry. Going in, I knew this would be a mountain to climb. But, if it happens, it will take a long time.

Last week, a trainer that bought my book told me that she gave copy to her partner, a real estate agent. That agent read it, then immediately bought copies for the ten realtors that work in her office.

I hope more of that happens. But hope is an opiate, not a strategy.

Which is why I need to move into other markets. And that’s going to be hard. Because when you change focus, you start over.

Once you’ve aligned your offering with the right audience, you’ll still face another challenge: the contextual nature of influence.

3. Influence: The contextual boundaries of your authority

In the fitness industry, I can get a lot of people to answer my messages. In other industries, not so much.

What we perceive as “global status” is actually a collection of micro-reputations, each confined to its own ecosystem. Your authority isn’t a portable asset you carry from space to space—it’s deeply embedded in the relationships, history, and social proof you’ve built within specific communities.

This isn’t just about fame or follower counts; it’s true for all forms of credibility:

- The respected professor who switches universities and has to re-establish classroom rapport

- The business leader who moves industries and finds their expertise questioned

- The community leader who moves homes and becomes just another neighbor

John Berardi sent me a text one day. He co-founded Precision Nutrition and sold it for close to $200M. The guy is now all-in on youth athletic coaching, starting over in a new field.

Something he said stuck with me:

“it’s interesting to note that when starting any new gig, you sorta start over the stages of yes from scratch…regardless of where you were at in your previous life.”

This reality hit me hard during my book launch. I got ignored by people I thought would respond—the self-publishing guru, the online course expert, the newsletter wizard. Each with smaller platforms than mine, but in their worlds, they mattered. And I didn’t.

A simple test confirmed this: I messaged someone on X (where I’m unknown) and got a thumbs up. I sent the same message on Instagram (where my follower count makes me look important), and suddenly they “loved my work” and wanted to “talk shop”. Even though they’d never heard of me before.

This isn’t cynical; it’s reality. We’re all simultaneously somebody and nobody, depending on where we stand.

Two key principles emerge:

1. Compound in one place: There’s immense value in building deep reputation in one field over time.

Reputation compounds when you stay consistent in a specific context.

2. Reset expectations when moving: If you choose to expand into new territories, be mentally prepared to be a beginner again.

Ask yourself: Can you separate your previously earned identity from your current status in a world where, once again, nobody gives a shit who you are?

I’m back to scratching and clawing.

Trying to make a name for myself again.

Back in the good old days I’d stay up late after clients and write articles in the corner of my one-bedroom apartment hoping, begging, anybody would pay attention.

Well, it’s 6am on a Sunday morning and here I am again––writing an article. Thinking not in weeks, months, or even years, but in decades. Hoping I can do it what I did in the fitness industry again but on a bigger, worldwide scale. Hella fun.

4. Mastery: The illusion of transferable excellence

This is embarrassing. But, whatever, here it goes:

I botched my podcast interviews.

Two of the bigger shows I was interviewed for sent a message on book launch day to say that the episode didn’t meet their quality standards and would not be published.

If you wake up in the morning and see a jerk, maybe you saw a jerk.

Then you go for a walk and see another jerk and I’ve got bad news for you, you’re the jerk.

I was pissed when it first happened, blaming the host.

When it happened again, I realized that I was the problem.

It hurt. I was pissed.

A few hours later, I put my ego aside and asked for feedback.

What he sent back hit me like a ton of bricks.

- I’m happy I asked for feedback.

- I’m grateful he gave me useful feedback.

How you practice is how you will perform.

Here’s what happened:

I’ve recorded over 1,000 podcasts. Figured I had it in the bag. I was going to go on all these shows and blow them away. I didn’t practice. Just went in there and ripped it.

That was a mistake because I’d been practicing the wrong way.

Over 800 of the podcast episodes I’d recorded were on my own show. The format of that show is designed around me speaking for 80-90% of the time.

Almost every interview for other shows I’ve ever done were ones from the fitness industry where I knew the host well. It was a natural conversation between friends.

Neither prepared me to be interviewed by well-prepared hosts to audiences who didn’t know me.

What looks like transferable expertise often contains hidden contextual elements we don’t recognize until we fail. The skills that make you exceptional in one environment may be precisely what undermines you in another.

Mastery is highly contextual.

There’s examples everywhere: The star employee who struggles after promotion to management, the successful small business owner who fails when scaling up, how bad of a basketball coach Michael Jordan was––all examples of how mastery in one context doesn’t automatically transfer to another.

Two lessons I can pull out here:

- Practice deliberately.

- Always ask for honest, uncomfortable feedback.

The mark of a true professional isn’t flawless performance in familiar territory—it’s the willingness to become a student again at the edges of your competence.

What happened sucks. I’m grateful it happened. It exposed me to an area of improvement.

Putting yourself out there and stretching at the edge of your comfort and competency will show you where you need to improve.

But there’s an even deeper lesson about expectations that completes this journey.

5. Self-reliance: The ultimate liberation

This final lesson was both the most painful and liberating.

It transcends creative work and touches on a fundamental truth about all human endeavors.

By and large, I was disappointed by the lack of support I got from colleagues and friends for my book launch. Not in every case, but in many cases.

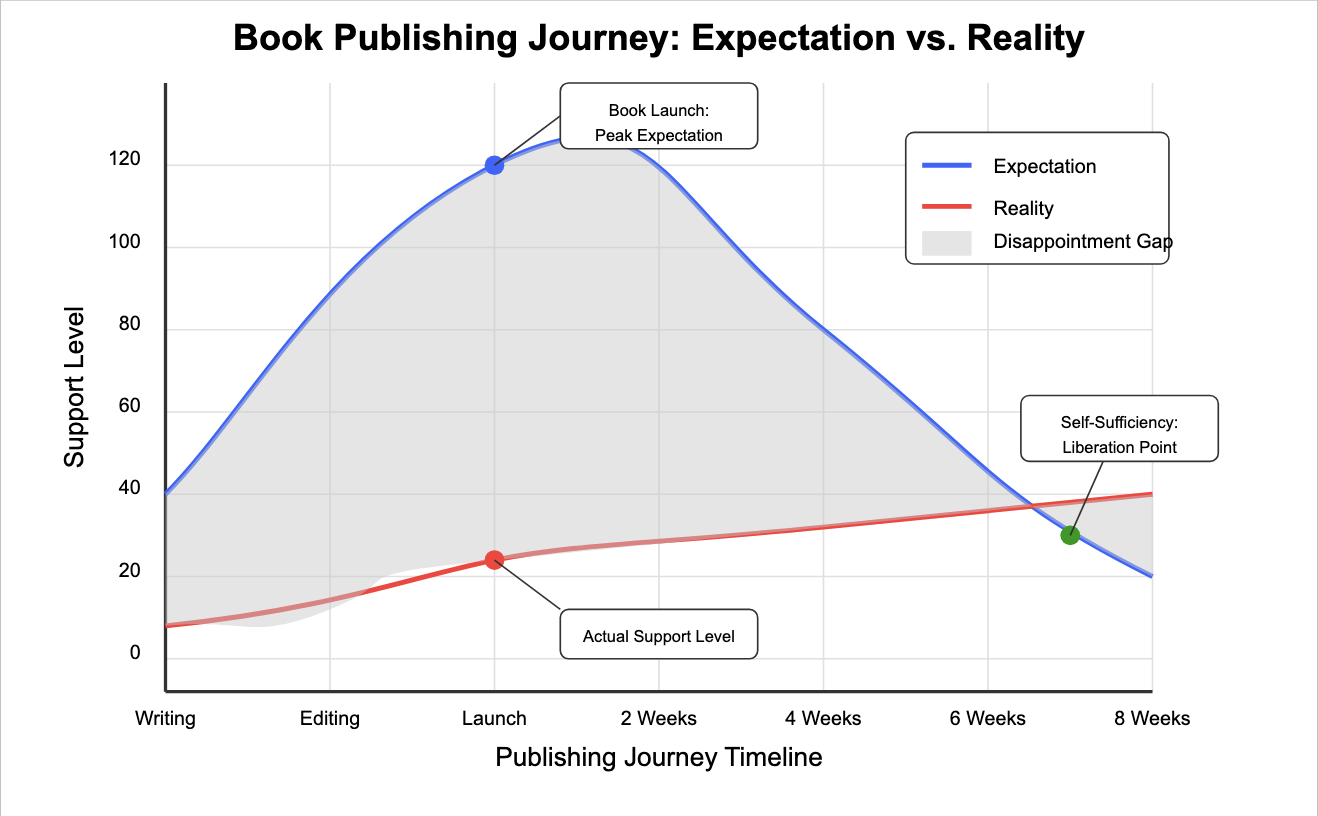

Call it the expectation-reality gap.

During the writing and editing process, friends and colleagues were in my corner, encouraging me on.

Then the book came out, a few showed up for me in big ways, most didn’t. The disappointment gap got huge.

We experience disappointment not because others fail us, but because our mental models don’t recognize that each person is the protagonist of their own story, not a supporting character in ours.

As time’s passed, the gap decreased. Perhaps that’s why I’m writing this article today. Liberated. Entering into self-sufficiency. Firmly appreciative that I’m on my own. That no white knight in shining armour is going to show up and make all my hopes and dreams come true. That it’s up to me, dammit. It’s up to me.

As I’ve moved through this disappointment, I’ve developed a three-part framework that might help you navigate your own expectation-reality gaps:

1. Acknowledge the Gap

-What specifically did you expect?

-What actually happened?

-What emotions did the gap between your expectations and reality trigger?

2. Extract the lessons

-What unrealistic expectations did you have?

-What aspects were in your control?

-What are you going to do differently next time?

3. Reframe the narrative

-How’s this experience going to serve your long-term growth.

-What surprising positives emerged?

-How’s this setback going to prepare you for future success?

—

This thing that I worked on for three years was a thing important to me.

Over those three years, my colleagues and friends were also working on things important to them.

I cannot realistically or justifiably expect them to care more about my thing then their thing. And everybody has things that are pressing for them at any given time.

We’re all too close to our own world, and too far away from others.

I don’t hold it against everybody. And I didn’t go into it expecting anybody to go out of their way and stop what they were doing to support me.

All of the stories I told myself about how I did nice things for them in the past are irrelevant. They’re rooted in my reality––in the stories I tell myself––not in the reality of others. I don’t know what’s going on in another’s world. I don’t know what they’re thinking, their struggles or stressors.

You can only control your efforts, and the intention behind your efforts.

You’re on your own isn’t cynical, it’s liberating. Getting to self-sufficiency is a painful process but I think that you’ll be happier with the trouble.

And when you do get there, you will also become genuinely appreciative of whatever support does materialize. It transforms unexpected assistance from an entitlement to a gift.

This perspective doesn’t mean we shouldn’t build communities or support systems. Instead, it means we build them authentically, without the hidden agenda of future reciprocity. Support others because it aligns with your values, not because you’re banking social capital.

—

I’m being hard on myself here. Harder than I should be. Truth is, I feel great. I’m on fire right now.

I did a thing.

It was hard.

And I crushed aspects of it.

I wrote an incredible book.

Moreso, I went all-in. Left it on the table.

I’m proud of what I did; happy for what it taught me.

And excited for how much better the next book will be. And the one after that. And the one after that. And that. And that.

I invite you to embrace your own expectation-reality gaps not as failures but as the necessary terrain between where you are and where you’re going.

The journey matters.

The learning matters.

And most importantly, your willingness to continue creating despite disappointment matters, perhaps more than anything else.

What you do for work isn’t a one and done. You can’t think like that.

You cannot think of your work as a series ten-day sprints. Or short-hit social media posts. You can’t even think even in years.

Instead, I invite you to think in decades. I invite you to be a grower.

-Jon

P.S. Can you think of one person to text or email this article to? Somebody who might benefit from it or resonate with it. If so, please pass it along. Thank you.

The post My book launch didn’t go all that well, really appeared first on The PTDC.